In the Book of the Dead, it is written that Ancient Egyptians believed all the deeds performed throughout a person’s life remain in their hearts. Thus, when a person died and their spirit travelled into Duat (The Underworld) where the heart would be judged in the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony, if they had lived a good life then their heart would weigh less than the feather of truth worn on the head of Ma’at, and the deceased would consequently be allowed to spend eternity with Isis and Osiris; but if they had lived a bad life then the heart would be heavy, and judgement fierce, taking the form of being thrown into the jaws of Ammit, the crocodile monster, where they would be devoured for eternity.

I love myth stories, especially if they contain a gruesome ending. However, the reason for relating this tale is not one of simple sensationalism. On first reading about the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony, two expressions stood out for me, ‘as light as a feather’ and ‘a heavy heart’; but could this ancient Egyptian myth really be the origin of these oft-used expressions of Country singers and obituary writers? Or do they have some other origin a bit closer to home.

Starting Points

First off, I am not suggesting that these modern English expressions are inherited undeviatingly from this Egyptian myth (so many ideas from ancient writing often reach us in indirect ways, going to ground for centuries before resurfacing in later eras), but it does afford me the opportunity of taking you on a hunt for clues (the origin of that word deserves a post all to itself), to uncover the beginnings of an expression still in common use today.

With a Heavy Heart.

The first point of call in investigating the provenance of any expression should be a good etymology dictionary. Here is what The American Heritage dictionary has to say on the subject of a heavy heart:

“Heavy Heart: In a sad or miserable state, unhappily, as in He left her with a heavy heart, wondering if she would ever recover . The adjective heavy has been used in the sense of “weighed down wit grief or sadness” since about 1300. Its antonym light dates from the same period. The latter use survives only in light heart , meaning “freedom from the weight of sorrow” that is, “a happy feeling.”

American Heritage

No examples are given to support the 1300 date, and no etymology is offered for ‘heavy heart’ itself; but at least we have a rough origin for ‘heavy’ in the expression.

The Good Book

Another port of call most certainly should be the Bible as it is one of the earliest English translated documents still in popular circulation. You can find on-line searchable databases of every printed edition of the Bible dating back to Wycliffe’s 14th Century translation on Biblegateway, which makes the job of the etymologist so much easier. The interested etymologist can also perfom cross reference searches of the various additions, which, in the case of ‘heavy heart’, throws out some interesting results:

The Biblegateway database contains the following:

| Wycliffe Bible

1 Samuel 6:6

Why make ye heavy your hearts, as Egypt and Pharaoh grieved their heart(s)? Whether not after that he was smitten, then he delivered God’s people, and they went forth? (Why be ye stubborn, or stiff-necked, like Egypt and Pharaoh were stubborn, or stiff-necked? For after God had struck them, did they not let God’s people go, and they went away?)

Psalm 4:2

Sons of men, how long be ye of heavy heart? why love ye vanity, and seek leasing? (Sons and daughters of men, how long shall ye insult me? why love ye empty and futile, or worthless, things, and go after lies?)

Matthew 26:37

And when he had taken Peter, and two sons of Zebedee, he began to be heavy and sorry [he began to be sorrowful and heavy in heart]. |

King James Version

1 Samuel 6:6

6 Wherefore then do ye harden your hearts, as the Egyptians and Pharaoh hardened their hearts? when he had wrought wonderfully among them, did they not let the people go, and they departed?

Psalm 4:2

2 O ye sons of men, how long will ye turn my glory into shame? how long will ye love vanity, and seek after leasing? Selah.

Matthew 26:37

37 And he took with him Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, and began to be sorrowful and very heavy. |

I have given the Wycliffe quotes alongside the King James Version to show that heavy heart was later changed to ‘harden your heart’ Samuel 6:6 ‘turn glory to shame’ Psalm 4:2 and ‘troubled’ or ‘anxious’ Matthew 26:37.

Interestingly we can also see a new addition of Heavy Heart in the New King James Version:

| Proverbs 25:20 Wycliffe Bible (WYC)

20 and loseth his mantle in the day of cold. Vinegar in a vessel of salt is he, that singeth songs to the worst heart. As a moth harmeth a cloth, and a worm harmeth a tree, so the sorrow of a man harmeth the heart. (Like him who taketh away a mantle on a cold day, and like vinegar in a vessel of salt, is he who singeth songs to an aggrieved heart. Like a moth harmeth a cloak, and a worm harmeth a tree, so a person’s sorrow harmeth his heart.) |

Proverbs 25:20 King James Version

Like one who takes away a garment in cold weather, And like vinegar on soda, Is one who sings songs to a heavy heart.

|

The King James version is a collection of various translations dating back at least as far as 1380 AD when John Wycliffe translated the Bible into English for the first time. We have no exact date for when these passages were translated though. Most modern English versions of the Bible seem to follow the translation of the King James version, using ‘heavy heart’ only in Proverbs 25:20, though Keil and Delitzsch’s Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament says that a more exact translation would be “a heart morally bad, here a heart badly disposed, one inclined to that which is evil.” None of the modern Bible versions follow Wycliffe’s use of ‘heavy heart’ suggesting either a fault in the early Wycliffe translations, or a change in the common usage and understanding of the expression over time. For an audience to understand Wycliffe’s usage of ‘Heavy Heart’, it required a common understanding of the term, thus suggesting it was used in common parlance.

The Bard

Another excellent source material to examine is Shakespeare. Shakespeare uses the combination of ‘heavy’ & ‘heart’ in a number of his plays.

All’s Well That ends Well

My heart is heavy and mine age is weak;

Grief would have tears, and sorrow bids me speak.

Love’s Labour’s Lost

Prepare, I say. I thank you, gracious lords,

For all your fair endeavors; and entreat,

Out of a new-sad soul, that you vouchsafe

In your rich wisdom to excuse or hide

The liberal opposition of our spirits,

If over-boldly we have borne ourselves

In the converse of breath: your gentleness

Was guilty of it. Farewell worthy lord!

A heavy heart bears not a nimble tongue:

Excuse me so, coming too short of thanks

For my great suit so easily obtain’d.

Much Ado About Nothing

God give me joy to wear it! for my heart is

exceeding heavy.

Othello

The time, the place, the torture: O, enforce it!

Myself will straight aboard: and to the state

This heavy act with heavy heart relate.

Richard II

Twice for one step I’ll groan, the way being short,

And piece the way out with a heavy heart.

Richard III

An if they live, I hope I need not fear.

But come, my lord; and with a heavy heart,

Thinking on them, go I unto the Tower.

Troilus and Cressida

What a pair of spectacles is here!

Let me embrace too. ‘O heart,’ as the goodly saying is,

‘—O heart, heavy heart,

Venus and Adonis

‘My tongue cannot express my grief for one,

And yet,’ quoth she, ‘behold two Adons dead!

My sighs are blown away, my salt tears gone,

Mine eyes are turn’d to fire, my heart to lead:

Heavy heart‘s lead, melt at mine eyes’ red fire!

So shall I die by drops of hot desire.

In all these examples, Heavy Heart suggests grief and misery, quite different from Wycliffe’s use of the expression to mean ‘hardening the heart’, ‘shame’ or ‘troubled’. Interestingly, Shakespear does use hard-hearted in Henry VI, Part III.

Henry VI, Part III

There, take the crown, and, with the crown, my curse;

And in thy need such comfort come to thee

As now I reap at thy too cruel hand!

Hard-hearted Clifford, take me from the world:

My soul to heaven, my blood upon your heads!

….and the Martyrs

The earliest quote I can source in Modern English for the exact term ‘heavy hearted’, outside of the Bible, is Foxe’s book of Martyrs (1563), an account of Protestant martyrs throughout Western history from the 1st century through the early 16th centuries, which contains the expression ‘with a heavy heart‘ in two places. I will give one example here:

“The father, on being dismissed by the tyrant Bonner, went home with a heavy heart, with his dying child, who did not survive many days the cruelties which had been afflicted on him.

Page 354 2007 reprint

If anyone has had a chance to look at this wonderful piece of Protestant propaganda, they will know it is full of the most horrific woodcuts displaying martyrs being killed in such gruesome ways that it would put most slasher movies to shame. Well worth a peak.

So, at this junction we have the following questions:

- Firstly, the expression ‘a heavy heart’ does not appear to be a true translation from the Bible text, but it appears in the King James Bible. Does this mean that perhaps the expression was well known enough to be used at the time of the translation? If this is the case, why is there not more writing containing ‘heavy heart’ between the 14th C. and the 16th C.?

- Secondly, did Foxe pick up on the phrase from a source, such as the King James Bible or from somewhere else?

- And finally, did Shakespeare get the expression from the King James Bible, from Foxe or somewhere else?

A sinking feeling

Have you ever heard it be said that a heart can break, or that a heart sinks when disappointed? The idea of the heart being the seat of personality and emotion seems so natural to us but, I would argue, it is a cultural construct. When you are sad you do not feel any ‘sinking’ feeling in your heart, or a ‘breaking’ at love lost. These are concepts ‘learned’ through culture. This statement can be supported by the fact that there are limited examples of ‘broken heart’ (circa. 1464) or ‘sinking heart’ (circa 1700s) in early writings, they are ideas that took off in literature during the romantic period. The examples of where the King James Bible uses ‘heavy heart’ are not direct translations from the original texts but rather substitutions for some other idiom particular to Hebrew. Substitution of idioms in translations would mean the contemporary audience for that work would already be familiar with the substituting idiom, otherwise it would lose all sense; so why are there no earlier sources in writing?

Before getting to that, I thought I would do a comparison with other languages that I am familiar with.

Cuore Pesante

Modern Italian does not use the heavy/light heart metaphor much. However, I have found references to it turning up in Italian literature from 1850, once in a discussion on Egyptian history:

Gli Egizii dicono dunque etscem, che letteralmente significa picciol cuore, ed esprime l’ idea di pauroso, codardo ; arsciet , cuore pesante oppure lento di cuore, cioe paziente; ssaciet, cuora alto o alto di cuore, orgogliosa; ssab.et, …

1834

In a medical text:

Cuore pesante 652 grammi. Idro-pericardite, vegetazioni sulle valvole aortiche e sulla mitrale , false membrane rivestenti l’interna superficie del ventricolo sinistro. Uomo di 22 anni, affetto già da sei anni di malattia di cuore in …1843

..and Biblical scholarly text:

… come erano insensati, ed il loro cuore pesante e tardo a credere quello che i Profeti dissero ; e per convii*- cerli incominciò da Mosè , e percorrendo appresso tutte le profezie, spiegò loro quello «he era stato predetto di lui 2. …

1822

Cœur Gros

In French ‘heavy heart’ translates as ‘cœur gros’ and this turns up in French texts from the 1560s onwards, mainly in Biblical texts and translations of Shakespeare. There are, however, a couple of examples of it used descriptively outside of these texts. For example:

Or, les Hespagnols , ayans le cœur gros à cause de leur victoire et acharnez à partuer le reste des François, braquèrent les canons du fort contre les navires et bat- teaux. Mais à cause du temps pluvieux et que les canons aussi …

Brief discovrs et histoire d’un voyage de quelques François en la Floride:

1579

In Spanish, ‘heavy heart’ translates just as ‘pesar’ (regret, sorrow). There is no correlation between them.

So, in Italian there is no real connection. However, French and English texts contain the expression from the 1500s onwards. I wonder why? A religious source seems likely, seeing as there is a mass of biblical writing from that time onwards which uses the expression in both French and English. That would seem plausible, but why just these two languages? What is the common thread? Could it in be connected to the Reformation, Henry VIII breaking from the Catholic Church, Protestantism? Is Foxe indeed the source?

The Seat of Emotion

The idea of the heart being the seat of emotion is one passed down to us from Ancient Greek thinkers. The most commonly held belief in ancient Greece was that the heart was the seat of thought and logic (sentience) as endorsed by Aristotle; Galen thought of the heart as a heat chamber where the soul most likely resides and that it controlled all other organs with an intelligence of its own. These ideas were based on misguided views on the development of human embryos and structures of the organs. They believed that the heart was the first organ to form in the body’s development, and, thus, it must be the seat of logic, thought and emotion [Hippocrates writings did contradict these views and locate pleasure, sensation and thoughts in the brain; however, he was an exception]. The faulty views of Aristotle and Galen stood as THE authority on the heart in Europe until about the Renaissance when it was finally possible for laymen to dissect corpses without fear of a visit from the inquisition or some other such church authority. Before that, knowledge of anatomy was confined to church scholars who did not make practical observation themselves. This thinking about anatomy led me to do some research into historical developments in the anatomy of the heart and I found some interesting things.

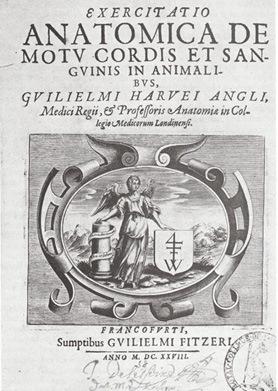

Enter William Harvey

It seems the belief that the heart was the seat of emotion continued up until the time of a certain William Harvey who was the first European to correctly map the heart and the flow of blood. De Motu Cordis, Harvey’s book outlining his views on the circulation of blood was not well received by his peers due to their persisting belief in Galen. Although Harvey did supported the Aristotelian notion of the heart, he carefully examined the function of all of its different parts and came to a reverse conclusion from that of Galen and his medieval and Renaissance readers: he believed that the heart was actively at work when it was small, hard and contracted (systole), expelling blood, and at rest when it was large and filled with blood (diastole). He wrote in 1653:

“The heart is situated at the 4th and 5th ribs. Therefore [it is] the principal part because [it is in] the principal place, as in the centre of a circle, the middle of the necessary body.”

Harvey did not challenge the metaphysical interpretation of the heart though. He agreed that the heart was the primary “spiritual member” of the body, thus the seat of all emotions (the idea of the ancient Greek thinkers). As a contemporary wrote:

“If indeed from the heart alone rise anger or passion, fear, terror, and sadness; if from it alone spring shame, delight, and joy, why should I say more?”

Andreas de Laguna in 1535.

Harvey metaphorically described the heart as the “king” or “sun” of the body to underscores its cosmological significance, an idea popular in religious iconography and alchemy.

This sudden renewed interest in anatomy at that time probably spiked interest in the popular imagination, and Harvey’s position as the King’s physician could account for his views coming to the churches attention. Educated men were more often than not church scholars, so the intertwining of science and religion would have been inevitable.

All the references to heavy and heart appear to start appearing at about the same time. I did some searches on variations of the ‘heavy heart’ theme such as ‘a heaviness of heart’ and it only seemed to confirm my suspicions. However, take note of my use of the word ‘seemed’…..

Heart to Hart

As is often the case with investigations of the origin of expressions, the researcher (in this case me) will come to a point in where their investigations will inevitably start going awry. This happened when I realised that Heart was not always spelt as such in English, but was for a long time written as ‘hart’. Initially I found a solitary earlier quote with this new spelling it 1587, from an Italian translation:

Amorous Fiammetta

Giovanni Boccaccio – 1587

Nor yet secure of her voluble and flattering Fortune, with howe heavy hart did shee celebrate her newe espousalles, which greefes and extreame myseries, with a tragicall ende at last, and with a stout enterprise, she did fully finish. …

As this is a translation from Italian, it does not necessarily mean that the original text contained the expression ‘heavy hart’ or ‘cuore pesante’; After all, in Italian, ‘cuore pesante’ actually means something closer to ‘sinking heart’ or ‘sinking feeling’. But this does appear to still locate the usage of the phrase in the English language around the same time as dissections were taking place in Bologna (where Harvey studied). Wiki has some interesting info regarding this:

The first major development in anatomy in Christian Europe, since the fall of Rome, occurred at Bologna in the 14th to 16th centuries, where a series of authors dissected cadavers and contributed to the accurate description of organs and the identification of their functions. Prominent among these anatomists were Mondino de Liuzzi and Alessandro Achillini.

The first challenges to the Galenic doctrine in Europe occurred in the 16th century. Thanks to the printing press, a collective effort proceeded across Europe to circulate the works of Galen and Avicenna and later publish criticisms on their works. Vesalius was the first to publish a treatise, De humani corporis fabrica, that challenged Galen “drawing for drawing” travelling all the way from Leuven[13] to Padua for permission to dissect victims from the gallows without fear of persecution. His drawings are triumphant descriptions of the, sometimes major, discrepancies between dogs and humans, showing superb drawing ability. Many later anatomists challenged Galen in their texts, though Galen reigned supreme for another century.

Wikipedia

Weighing my Options

I started this investigation to see if a heavy heart came into the English Language from the Egyptian Book of the dead. Unfortunately it’s looking highly likely that the Egyptian myth was a red herring and had nothing to do with the expression after all. I have also shown that it was used in Wycliffe’s Bible, but not in later editions, suggesting a mis-translation of Hebrew. So, some pertinent questions raised are:

- Why is there an absence of the expression in written print from the 14th Century to the 16th Century?

- Was the re-emergence in the 16th Century due to the renewed interest in anatomy?

And this is where the Archaic English spelling comes in. I already mentioned that heart was often written as hart, but imagine my surprise when I find that heavy could be written as heauvy.

In the book The Facts on File Dictionary of Proverbs a number of quotes are given that fill in this 14th-16th Century gap in the record.

“The proverb [[a light purse makes a heavy heart]] was first recorded in 1555 by J. Heywood.”

An early edition of The Oxford English Dictionary also offers the following information:

HEAVY-HEARTED: Proceeding from or caused by a heavy heart; sad, doleful.

1562 “Lyght purses Make heauy hartes, and heuy harted curses.”—Proverbs and Epigrams (1867) by John Heywood, page 151

HEAVY-HEARTED: Having a heavy heart; grieved, sad, melancholy.

circa 1400 “Heuy herted men and stille studious men.”—Cato’s Morals 235 in Cursor Mundi: A Northumbrian Poem of the 14th Century, page 1672

1535 “Thou art not sicke, that is not ye matter, but thou art heuy harted.”— Coverdale Bible, Neh. ii. page 2

So we can now see that the earliest quote I have been able to faithfully source is the Wycliffe bible text (an early OED gives a c.1400 quote from a book of Northumbrian poems which I am unable to track down), and, despite the apparent two-century gap in the source material, there is indeed an abundance of intermediary sources with alternative spellings dating up to that crucial 16th Century marker when the expression started to appear both as a metaphor for sad and as a scientific measurement of a heart engorged with blood.